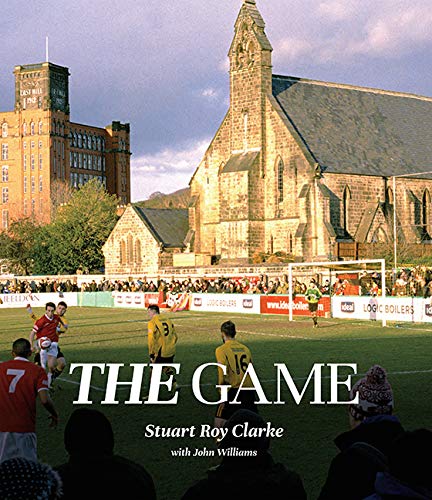

The Game by Stuart Roy Clarke, with contributions by John Williams, is a new pictorial book that is essentially an epic, feature-length love letter to British soccer. Clarke is a renowned soccer photographer in England who has chronicled the sport for the past three decades via old-school still photography in books and his popular traveling exhibition called “Homes of Football.”

The Game is roughly divided into two sections. The first is a conversational-style back and forth between Clarke and John Williams (no, not the movie score maestro). Williams is a sports sociology professor at the University of Leicester.

Their conversation is a relaxed, approachable analysis of British soccer culture. To their credit, though the book is aimed at a North American audience, it doesn’t talk down to the reader as some soccer books tend to do here (i.e. “A corner kick occurs when…”).

Clarke and Williams’ discussion runs the gamut: the attraction of international TV audiences to British match atmosphere; the uniqueness of away fan culture in Britain; the magic of the FA Cup as a sort of bridge to the British game’s past; the stadium tragedies that ended the old terrace era; the importance of Leicester City’s insane 2016 title run.

One chapter titled “The Attendance Is Important” is now relevant in a way the authors couldn’t have imagined when writing it. The end result of the book is like sitting in an English pub, eavesdropping on a thorough social history tour of British football from two guys who really know their stuff.

At first glance, I thought I was going to be disappointed with the size of many of Clarke’s photos in this section, but the smaller photos end up working well to punctuate their conversation.

And there are also multiple fascinating photos in this section that Clarke didn’t take, from before his time, including the not-to-be-missed aerial shot of East London’s Hackney Marshes (a heavenly view).

Clarke obviously loves an old soccer ground. For true soccer nerds, there’s a certain beauty to empty soccer stadiums. But only when there’s not a match being played. An empty soccer stadium during a match – as any FC Dallas fan can attest – is rather deflating.

Clarke has multiple charming shots of empty stadiums receiving repairs or having the grass cut. But the beauty is always informed by the knowledge of the matches that have taken place there and the fans who reveled in them, and by the anticipation of future matches that will breathe life into the place.

There’s a certain pain to the current matches being played in empty stadiums. Premier League teams covered the empty seats in creative, colorful tarps – almost as if they couldn’t bear to show you there are no people there. The vast, silent void of these venues is so odd and uncomfortable that they just have to cover the evidence of the emptiness.

There has always been a symbiotic relationship between the game being played and the people watching it. Clarke inhabits this symbiosis with his camera. Is the heart cut out of soccer when there is no crowd? Judging by most of Clarke’s vibrant photographs in The Game, you might be tempted to answer yes to that question.

But then you find the answer is ultimately no – because of Clarke’s photos of rural games, a farmer in coat and cap with dog on a leash watching a game by the corner flag; or a few shirtless observers lounging on the late-summer grass taking in a match with rolling foothills looming over the green space. That’s the heart of soccer too, playing for no money, no crowds, no glory – purely for the love and enjoyment of the game. Clarke clearly loves both sides of the coin.

In a chapter titled “Fans Needed,” Clarke writes: “British football fandom has always been, at some level, about embracing suffering – proving your devotion, as you wait for the good times to come. By contrast, the USA’s attempt at establishing ‘soccer’ never went down the smoking and suffering route: they just introduced popcorn instead.”

Clarke aptly nails overall U.S. soccer culture. Ours is a franchise culture – one that doomed the old NASL – and one that now pops another $100 million franchise off the MLS conveyor belt every season. And while we can appreciate to a certain degree the growth of the game this largesse represents, there is also an artificiality to it. These teams aren’t really birthed and nurtured on a local level. There are no real roots for many MLS teams. And it’s odd to see an Atlanta United win MLS Cup in just its second season – certainly no “suffering route” there.

That’s one of the things I find so fascinating about the British game, and why this book is so enjoyable for serious American soccer fans. It’s like finding a guidebook to a lost civilization, one where soccer is deep-rooted and king of the hill in a way American soccer fans could only dream of.

There is a surprisingly long history of soccer on these shores, but it’s very fractured and for long periods almost an underground scene. Many of our cities have deep professional soccer histories, but it’s a patchwork of clubs and stadia, fits and starts, rather than the British standard of century-plus-old clubs playing in roughly the same spot they’ve always played.

Clarke’s rich photographs alone are worth the effort here, but the book is also peppered with unexpected extras, like a giant timeline of British football history. The timeline is packed with great tidbits like the entry for 1912: “The laws prohibit goalkeepers from handling the ball outside the penalty area; previously, they could handle the ball anywhere in their own half.”

Clarke also includes an all-time English League Table – the top 50 teams in the land according to their cumulation of league table positions from 1888-2020. No spoilers here, except to say that you may be surprised who’s number one all-time. That club’s angst-ridden fans should count their blessings a bit more.

The book’s second half is devoted to an exquisite selection of Clarke’s most popular photographs, followed by some of his personal favorites. This half is the main attraction. Clarke really captures the startling transition from the old version of the British game to the modern Premier League that the world knows and loves.

A prime example is a dreary photo of a fan at the old Brighton and Hove Albion stadium in 1991, apparently injured, being led out of the stadium through the standing terrace end which is crumbling and closed-off to fans. Clarke reveals a grit, grime, and charm that we don’t see on this side of the pond via the slick modern Premier League coverage.

Clarke has a wonderful eye for capturing both the grandeur of club grounds across Britain and the humorous, oddball, human moments that enliven them. There’s the classic brick architecture of Aston Villa’s stadium; the quirky away-fan caravans; the chaos at Manchester City in 2012, moments after the stoppage time goal that ripped the Premier League trophy from Sir Alex’s hands.

One of my favorite photos in the book is a 1995 shot of a game between Hibernian and Heart of Midlothian in Edinburgh, with magnificent, craggy mountains rising over the stadium rafters.

Because it’s largely a book of photographs, many would describe this as a coffee-table book. But that often implies an artsy inaccessibility, and The Game is just the opposite. It’s a book to really sink into an armchair and take your sweet time with.

The Game might seem like an un-catchy title for a book like this, perhaps too generic, too vague. But by the end of Clarke’s marvelous photographic tour, you ultimately realize it’s an apt title because the book makes clear that in the UK, soccer/football’s status as THE game is unrivaled.

On the title page, Clarke writes: “In putting together this book, I asked myself of each page, ‘Will this make you smile in North America?’”

The answer is a resounding “yes.”