Back in the early 90s, while I was working in Manhattan, Dallas was announced as the 10th and final MLS club. My enthusiasm for the return of professional soccer to the U.S. was, by most accounts, annoying to my co-workers. I even made a $1 million bet with one of them who predicted the league wouldn’t be around in 20 years.

No, I’ve not been able to collect on that.

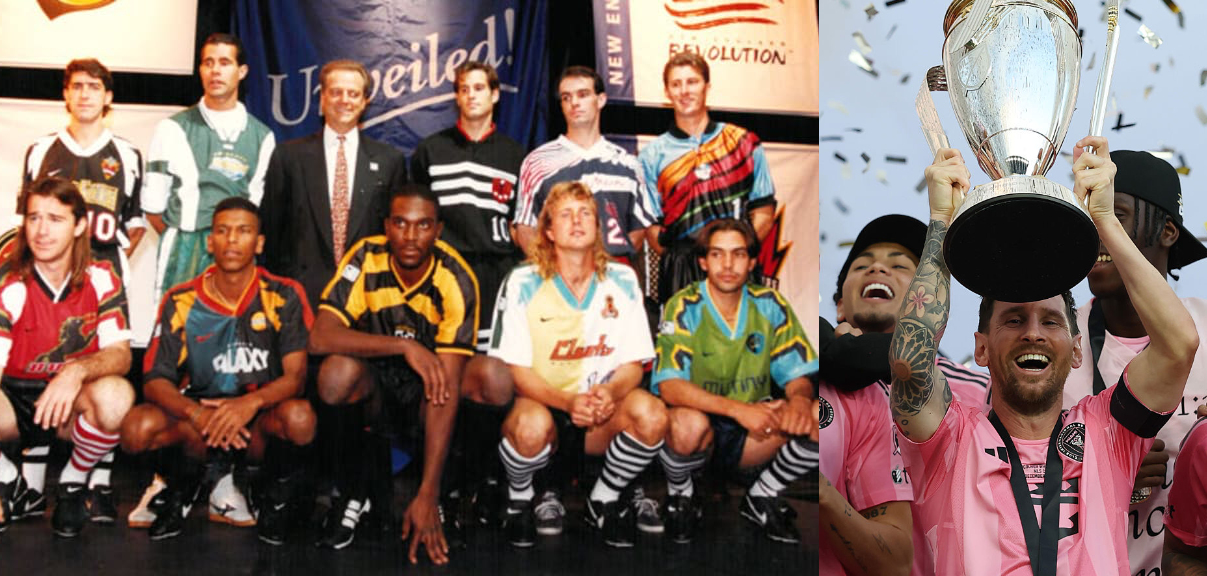

Here we are 30 years later and not only is the league still standing, but last weekend the game’s greatest ever, Messi, looked genuinely pleased with himself as he lifted MLS Cup and danced in a locker room champagne shower. For anyone who has lived the full arc of this league, there was something surreal about watching that moment unfold. It was a reminder of how far Major League Soccer has traveled from those early days when even suggesting the game’s greatest would one day play in the league, much less lift an MLS trophy would have felt as absurd as that million-dollar office bet.

While there are a lot of varied and valid opinions about Major League Soccer, as a member of the “Day One Club,” seeing all of that just warmed my well-dented heart and raised a simple question. What has 30 years of this actually delivered?

I’ll start with the thing I least understood back when all of this started. MLS’ expansion, growth, and influence on American soccer culture has been significant, but also divisive in ways that have turned genuinely toxic. The league’s structure, more business first than sporting focused, has divided a potential fanbase. From its single entity foundation, to its lack of promotion and relegation, the sport’s ‘third rail’, these choices supply the fuel that powers not only the league’s very active critics, but more importantly a worrying percentage of American soccer fans who are simply apathetic to it all.

I would have laughed at you in 1996 if you told me that over 30 years MLS would deliver a wildly successful amount of progress across player development, stadium construction, marketing power, tripling the size of the league, and placing several clubs among the world’s most valuable. Yet it would, by many, still be considered at best a curiosity and at worst a giant scam cosplaying as a major league.

Even so, it is difficult to sketch an alternate universe where MLS never launches in 1996 and what American soccer might look like in 2025. I suspect it would resemble some version of today’s USL, a minor league with a big heart and good intentions, but even further off the American sports radar than the fringy edge MLS has earned after all this time.

The growth of MLS coincided with, and in large part contributed to, the increased availability of the world’s established leagues in American homes and pockets. Being able to consume more Premier League matches in the U.S. than viewers are allowed to in England can partially trace its origins to MLS’ earliest television deals and the need to supplement broadcast schedules while giving Americans a peek into what all of this should look like.

Ironically, this has also created its own greatest competitor. With the entire world’s game now readily available through subscriptions, MLS’ position in the battle for the American entertainment dollar may also be its biggest burden.

I gave up long ago on trying to sell MLS to anyone. Convincing soccer-curious Americans to embrace an American version of the sport on its own terms often feels harder than it should. It’s as if I’m a “Flat Earther” when I suggest that an American version of soccer can be unique and special without parroting models and structures that have produced financial losses, widening gaps between clubs, and competitive imbalance. Yes, those systems created generations of history, I love them too, but they also resemble a juggernaut leaking oil at a precipitous rate.

Soccer in America does not have to be that, and for many well-trodden financial and cultural reasons, it should not. Whatever the sport matures into over the next 30 years, it needs to be different because it can never, ever be everyone else’s futbol.

That’s the leaguewide story. For me, it all comes down to one thing: MLS gave me my club. When I travel and am asked who my club is, despite also being a Manchester United fan of 30 odd years, my answer is always “Dallas”. From attending those early days of Dallas Burn games in mostly empty NFL stadiums to being there on a freezing night at a random Indianapolis university for the 1997 U.S. Open Cup Final, MLS fed me my first real experience of supporting a team and winning something tangible. I’ve seen United lift countless trophies, but never in person. That attachment is adopted. Dallas was inherited. Those early days, and that night in particular, taught me what this is really about.

For those of us who have been around since the start, following the Burn and now FC Dallas has meant decades of frustration, change, and recalibration. The origins of the Burn have mostly been forgotten; no specific owner, a compact staff and tiny fanbase trying to make soccer that drew less than 15,000 in a 72,500 seat Cotton Bowl something worthy of an entertainment dollar felt like climbing up a down escalator.

It was a gift when Lamar Hunt later rescued the club. That rescue also brought an ownership family deeply versed in professional sports, profit and loss discipline, and financial stability. It was a steady hand that ensured survival, even if it would later become a source of sporting frustration. Sure, there is a very successful and profitable youth operation, but as one of the original MLS 10, the lack of an MLS Cup stings.

When the club moved to Frisco, it was both survival and foresight. In the early 2000s, the demand for an urban core stadium was impossible. The league was too unstable, and it took the ambition and belief of a small municipality and an owner willing to take a risk to build what became Pizza Hut Park. What once felt like it may as well have been on the moon now sits in the middle of some of the country’s most serious growth. If it is good enough for the Dallas Cowboys, Toyota North America, the PGA headquarters, Dude Perfect, and three million residents within twenty miles, it is good enough for MLS.

Lamar Hunt is somewhere having a good laugh.

What has 30 years of this delivered? Perspective. There is something strange about watching the league mature while losing some of its early weird charm. Watching it balance sustainability while reaching for something bigger feels a bit like the harrowing watch as your 16-year-old drive off alone for the first time. Realizing those early dreams of being a world “Top 5 league”, or whatever, was always folly. I now understand it isn’t even the point.

Major League Soccer and FC Dallas often frustrate me and periodically test my loyalty. That feeling is not far off from how I feel about my Dallas Cowboys or Manchester United. When I place MLS and FC Dallas alongside those sputtering institutions, I realize that this is simply sports and being a sports fan.

Maybe that is what 30 years of Major League Soccer has ultimately given us. Another imperfect sports institution to attach our emotions to, complain about endlessly, and keep showing up for anyway.

Even Messi could not resist.

I feel all the emotions mentioned in the article. As a fellow day one fan, I applaud how faithfully you write about the arc of the past 30 years. Thanks!